It is one of my many quirks that when I start to write about

a small subject, Ruthwell Cross, located in a local area, the northern border

of the Kingdom of Northumbria, I like to take a step back. For serious

historians, my broad-brush stroke synopsis is probably laughable. For me it is helpful. I am picking a random year, say AD 710 as my

anchor.

Jerusalem had become a Christian city from the 200s to the

600s. There were Jewish communities in Palestine and Syria, but Jerusalem was

not one of them. In 614 Jerusalem was captured by the Persians during the

Byzantine-Sasanian Wars of 602-628. The Persian troops were accompanied by

Jewish forces from Galilee north of Jerusalem and forces south of

Jerusalem. Byzantium had become

increasingly anti-Jewish, continuing to forbid Jews access to Jerusalem except

on a very limited basis. In this

period, the concept that Jews were Christ-killers developed strong roots that

would last for millennia. Byzantine rulers had persecuted and oppressed the

Jews. The combined Persian and Jewish

forces besieged and captured Jerusalem without a battle. Thousands of Christians within Jerusalem were

killed, though the numbers are debatable. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was

damaged by fire and the True Cross carried off by the Persians as a war trophy.

A century before 710, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius was

crowned in 610. He strengthen the walls

of Constantinople and rebuilt the Byzantine armies, withstanding the siege of

Constantinople of 626 by Avars. As the

attention of Byzantium was focused to the east, Avars and other slavs moved south

of the Danube into the Balkan peninsula.

At this time, the Lombards settled in northern Italy in land that had

been controlled by the Ostrogoths.

Eventually Heraclius defeated the Persians and recaptured

Jerusalem in 627. As part of the peace settlement, a wooden cross, supposedly

the True Cross, was returned to the Emperor Heraclius in 628. With great celebration, the Cross was

returned to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in 629 or 630. Legend tells that Heraclius walked barefoot

and carried the cross into Jerusalem.

Heraclius carrying True Cross at the

gate of Jerusalem, in William of Tyre, Historia

rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum.

Book made in Bourges, France about 1480. British Library Royal 15 E 1 f.16.

http://www.bl.uk/IllImages/Ekta/mid/E115/E115495.jpg

Byzantine control over Jerusalem and the Holy Land was very

short-lived. The Rashidun Caliphate established after the death of the Prophet

Mohammed in 632 quickly conquered the Persian Empire, Mesopotamia, the Levant

including Palestine and Syria, Egypt and much of north Africa. The Caliphate

took control of Cyprus, Crete, Rhodes and raided Sicily. The successor Umayyad Caliphate continued the

conquest of north Africa and Anatolia.

All the eastern two-thirds of the Mediterranean Sea and adjoining lands came

under Muslim control.

In the western Mediterranean, the Visigoths had established

control over the Iberian Peninsula, as well as Aquitania and the area around

Toulouse. By 710, the Kingdom of the Visigoths

was fractured with internal division.

Beginning in 711, Hispania was invaded by Berber Muslims from north

Africa under Tariq ibn Ziyad. The

Umayyad conquest of Hispania would be complete except for the far north and

west, and extend into southern France and include much of the western coastline

of what is now France.

This would have profound impact on travelers and pilgrims

from the British Isles to Rome and beyond. Instead of travelling part of the journey

down the Rhone valley to Marseilles and then to Ostia, the port of Rome, by ship,

the traveler had to take the long overland route through the Alps.

In 990, the

Archbishop of Canterbury, Sigeric, kept a record of his trip to Rome to collect

his pallium. He recorded the churches

and sites he visited Rome and then the route he took from Rome back to

Canterbury. It is assumed that he took approximately the same route to Rome.[i]

Map of the locations

of the some of the stops on the route of Archbishop Sigeric in year 990.

In 710, what is now France, Belgium, Netherlands and western

Germany was under the Merovingian kings of Austrasia, Neustria, Swabia and the

dukes of Aquitania. The remainder of south-eastern France was under the control

of the Burgundians.

The Italian peninsula was divided between the Byzantine

empire and the Lombards. Constantinople

controlled the Exarchate of Ravenna and the Duchy of Rome and the far south of

the peninsula now Calabria, part of Campania, Basilicata and Apulia. The

Lombardian kingdom controlled north Italy as well as the Duchies of Spoleto and

Benevento.

Anglo-Saxon England was divided into seven kingdoms called

the Heptarchy-Kent, Essex, Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria. Dumnonia covered what is now Cornwall and

Devon. The Picts controlled the area

north of the Firth of Forth. There were

Welsh clans, and other Celtic groups lived west of Northumbria. In the 100 years since Augustine and his

company of monks was sent by Pope Gregory, most of the Anglo-Saxon groups had

become Christians following the Roman traditions though the older Celtic

Christianity still survived even after the Synod at Whitby in 664.

AD 710 was marked by continued warfare among

the kingdoms. Ine of Wessex and Northelm of Sussex were campaigning against the

Britons of Dumnonia. Beorhtfrith described as a prefect of Northumbria fought

the Picts in what in now Scotland. Since I will spend some time discussing crosses in Northumbria, I should mention that the two northern kingdoms of the Angles, Bernicia and Deira had been more or less united for a century under the Bernician king Aethelfrith (d. c. 616) forming the kingdom of Northumbria. Aethelfrith's daughter, Aebba, converted to Celtic Christianity while living in exile in Dal Riata, the Gaelic kingdom of western Scotland and northern Ireland. She established a nunnery about 660 at Ebchester, bringing Christianity to the previously pagan Angles.

The last half of the 500s and 600s also saw the

establishment of many monasteries that would influence Christianity in the

British Isles for centuries. What follows is my no means a complete list of the

abbeys and the monasteries and convents associated with the abbeys. I wanted to

highlight a few.

According to tradition, Iona was founded on the Isle of Mull

off the west coast of Scotland about 561 by Columba and twelve companions. This

monastery is usually credited with the production of the gospel Book of Kells

about 800 using the Vulgate Latin translation of Jerome.

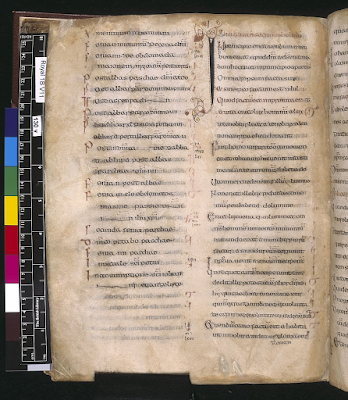

[Since the

illuminations of the Evangelists and the carpet pages of most of the books that

I am about to write about are so well known, I have chosen to show the

illuminations for the beginning of John. John 1.1: In principio erat Verbum et Verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat Verbum.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

Most of these examples show the elaborate interlacing for which these

manuscripts are renowned.]

Trinity College Dublin MS 58. The Book of Kells, f.292r. John 1.1. It is a mostly Vulgate text. Made in a Columban monastery about 800.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8e/KellsFol292rIncipJohn.jpg

See also: http://digitalcollections.tcd.ie/home/index.php?DRIS_ID=MS58_003v

The monastery at the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne was founded off

the east coast of Scotland by Aidan from Iona at the invitation of King Oswald

of Northumbria about 634. Lindisfarne was also the seat of the bishop. Perhaps

the most famous of the early bishop-abbots of Lindisfarne was Cuthbert (c.

634-687) whose remains are now in Durham Cathedral. A book of the Gospel of John was founded in

the coffin of St. Cuthbert when it was opened in 1104. Cuthbert died at Lindisfarne 687 and was

buried there. In 698 the monks thought

that a more important grave site was due St. Cuthbert because of the miracles ascribed

to him, so his body was reinterred.

The Gospel Book of John dates to 690-700 or so

and was made during the same time period as the more famous Lindisfarne

Gospels. Some time about 700 and perhaps as early as 698, the

Gospel Book of St. Cuthbert, must have been put inside the coffin. Abbot-Bishop Cuthbert’s remains and those of

Abbot-Bishop Eadfrith who was the scribe for the Lindisfarne gospels were

removed from the island after the Viking raid of 793 to the mainland of Northumbria, now Scotland. Cuthbert’s bodily remains were sent to several

places before coming to rest at Durham Cathedral in 995. In 1093, the foundation stone was placed for

a Norman or Romanesque cathedral at Durham.

In 1104, the shrine for St. Cuthbert’s relics was complete. It was then that the Gospel Book was found

when the coffin was opened.

British Library Add MS 89000. Gospel book of St.

Cuthbert. f.1r Made in Northunbria

The Gospel of John was made in the late 7th or early 8th century,

http://julianharrison.typepad.com/.a/6a013488b55a86970c019b03463506970d-500wi

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_89000_fs001r

The most famous of the manuscripts produced at Lindisfarne

was the Lindisfarne Gospels. The colophon at the end of the manuscript at f.259r, states that the manuscript was written by Eadfrith, bishop of Lindisfarne. This dates to manuscript to sometime between 698

and Eadfrith’s death about 721. So, for

the sake of this note, one could say that the Lindisfarne Gospels were being

produced in 710.

British Library MS Cotton Nero D IV. f.209v. John the Evangelist.

https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/236x/e8/0b/8c/e80b8c5f305b30f21c379e3511b45298.jpg

Intricate interlacing

of carpet page for gospel of John. British Library Cotton Nero D IV f.210v.

http://imageweb-cdn.magnoliasoft.net/britishlibrary/supersize/pod87.jpg

Lindisfarne MS Cotton

Nero D IV f.211r, John 1.1

http://www.oberlin.edu/images/Art315/13494.JPG

The first church founded in Kent was St. Martin’s Church. It

was founded by Queen Bertha, the Christian wife of the pagan King Æthelberht about 580.

This parish is still in existence and thus is one of the oldest churches in

continuous use in western Europe. When

Augustine arrived in 597 he used this church as his headquarters before

building the new cathedral and establishing the Abbey of St. Peter and St Paul,

later named St. Augustine’s Abbey.

Roman bricks re-used (spolia) in

the wall of St. Martin’s Church at Canterbury, Kent.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a9/Canterbury_St_Martin_chancel_wall.jpg/220px-Canterbury_St_Martin_chancel_wall.jpg

The church that became Canterbury Cathedral had a

Benedictine Abbey adjoined to it about 995. The impetus for the

foundation of the Abbey seems to have the administrative reforms of Archbishop

Dunstan who died in 988. Many

manuscripts thought to have been made in southeastern England are ascribed to

Christ Church Abbey.

Bishop Birinus, a Frank, was a missionary to the West Saxons

initially under King Cynegils in the 635.

The king gave him Rochester to be his bishopric. Later under King Cenwahl, the Old Minster at

Winchester was founded about 650. A priory was added sometime in the 10th

century and it also was a major site for manuscript production. (Much more to

come on “Winchester style.”)

Most of the oldest surviving Anglo-Saxon manuscripts come

from the monasteries in Northumbria. The founding of these institutions during

the late 7th century provides some interest glimpses into the

history of the British Isles in what is usually considered the Dark Ages.

As noted previously Benedict Biscop founded St. Peter’s

Abbey in Monkwearmouth, Northumbria, in 674 on land given to him by King

Egfrid or Ecgfrith. About eight years later, St. Paul’s Abbey at Jarrow was founded by twenty

monks from Wearmouth including the young Bede. Jarrow is about eight miles from

Wearmouth even though they are considered twin institutions. The first abbot at

Jarrow was Ceolfrith. Biscop brought in stonemasons and glaziers from Francia

to build the churches and buildings in stone and include glass in the

windows. As noted previously Biscop brought

home books and icons and other goods from his travels to furnish the libraries

of Wearmouth and Jarrow. In the year

710, the three large bibles associated with Wearmouth-Jarrow were being made

including the Codex Amiatinus that Abbot Ceolfrith was carrying to Rome when he

died. Another gospel book of which only

fragments remain is the Northumbrian Gospel Book at Cambridge, Corpus Christi

College 197B. It also seems to date from the 8th century and

displays the same elaborate interlacing seen in the other northern bibles or

gospel books except the Codex Amiantinus.

The Northumbrian Gospels, Cambridge Corpus Christi College 197B, p.247. John 1.1

http://dms.stanford.edu/image/qw038wz9710/197B_247_TC_46/small

The Abbey of St. Peter and St. Paul, later known as the

Abbey of St Augustine was founded by Augustine and his accompanying monks in

598. The first five Archbishops of Canterbury were Augustine (d. 605) and the

men that accompanied him, namely Laurence (d. 619), Mellitus (d. 624), Honorius

(d. 653). Then came Deusdedit who was

the first native born Archbishop. Not much is known about him though he

established a nunnery in Kent at the Isle of Thenet and the Peterborough Abbey.

He died about 664 or so since his name does not appear among those that

attended the Synod of Whitby. He may have died from the plague. According to Bede, his successor was Wighard

or Wigheard who died in Rome before his consecration of the same disease. This

allowed Pope Vitalian (d. 672) to choose an Archbishop from among the clergy in

Italy and to send with him a learned man to become the Abbot of St. Augustine’s

Abbey.

Pope Vitalian consecrated Theodore of Tarsus in 668 as the

Archbishop of Canterbury. He was a

Byzantine Greek, fluent in Greek and Latin. He brought a tradition of classical

learning and scholarship to Canterbury until his death in 690. He began his years as Archbishop by spending

time conducting a survey of British churches, appointing Bishops, and

instituting administrative reforms such as the division of the large diocese of

Northumbria, confirming the dating of Easter, limiting movement of monks and

clerics, regulating marriage and divorce, convening of regular synods, and

rules “intended to insure unanimity…of orthodox beliefs.”[ii]

Theodore had a rocky working relationship with one of his bishops, Wilfred, Bishop of York. Wilfrid became abbot at Ripon in 660. About 664 Wilfrid was appointed to be Bishop

of York. He went to Gaul to be

consecrated, staying for three years, and in his absence, another man Ceadda or Chad was appointed

Bishop of York. (Chad

resigned the see and went on to become the Bishop of Mercia and Lindsey at

Lichfield.) When Theodore took over as Archbishop of Canterbury he affirmed Wilfrid as Bishop of York. Bishop Wilfrid took his complaint against King Egfrid or Ecgfrith to Rome in 679. While he was in Rome, Wilfrid's signature appears on Pope Agatho’s Italian Synod of 680, representing Britain. Wilfrid won his appeal but King Ecgrith would not take him back as bishop. In the meantime, Theodore divided the Northumbrian diocese into three parts. Wilfrid eventually regained

the much smaller Bishopic of York along with the monasteries at York, Hexham and Ripon before his death

in 710. There is no written information about what Wilfrid brought back from

his trip(s) to Rome but, surely, he brought back at least some manuscripts.

Archbishop Theodore was accompanied by Hadrian or

Adrian. Hadrian was north African,

perhaps Berber, in descent who went to Rome probably because of the Arab Muslim

conquests of north Africa. He had been to France on more than one occasion

before he accompanied Theodore to Canterbury. Hadrian was abbot of a monastery in or near

Naples. When Theodore and Hadrian left Rome, they traveled by sea to Marseille

before going overland. They were accompanied for most of the trip by Benedict

Biscop who was returning from Rome to Northumbria. Theodore and Hadrian made it as far as Arles

in southern France before being detained by Ebroin, Mayor of the Palace of

Neustria. Ebroin did assert some control over Burgundy in about 668 but it is

not clear if his control extended so far south.

In any case, Theodore and Hadrian were detained and had to obtain

permission to cross Neustria. This took some time so that Theodore made it only

to Paris by wintertime which he spent with the Bishop of Paris. In springtime,

Theodore was sent for by King Ecgberht or Egbert of Kent. Theodore arrived in Canterbury in the spring

of 669, already 67 years old. Theodore was archbishop for 21 years.

Hadrian was detained perhaps because he was north African

and suspected of being a spy for the Byzantine Emperor Constans II who was

living at the time at Syracuse, Sicily.

Eventually Hadrian made it north as well after spending the time with

the bishops of Sens and Meaux. He

probably arrived at Canterbury a year after Theodore in 670. Soon after his arrival, Hadrian became Abbot

of the Abbey of St. Peter and St. Paul, later St. Augustine. Benedict Biscop served

as Abbot in Hadrian’s place. Once Hadrian arrived at the Abbey, he began his work as teacher and administrator. Abbot

Hadrian obtained a papal privilege from Pope Agatho that prevented outside

inference with the affairs of the monastery. (Ceolfirth obtained a similar

letter of immunity from Pope Sergius I for Monkwearmouth-Jarrow.) Theodore and Hadrian started the school at

Canterbury that quickly became renown for the teaching of Greek and Latin. We

know something of the teaching of the Old and New Testament to the students at

the school thanks of a manuscript Biblioteca Ambrosiana M.79 sup. in Milan, translated

as Biblical Commentaries from the Canterbury School of Theodore and Hadrian.

Hadrian died in 709 or 710 after having served as abbot at Canterbury of almost

40 years.

As the late Rev Dr. Richard Pfaff pointed out in The Liturgy in Medieval England: A History, there is precious little evidence on which to base a reconstruction of the liturgical materials, bibles or gospel books available in the 7th, even early 8th century England. The Vulgate translations of the gospels in the Gospels of St. Augustine (Corpus Christi College Cambridge 286) is an Italian manuscript from the 6th century that may have accompanied the Gregorian mission to Kent. But after that, there is not much surviving material on which to write a story about the links between the waning antique Roman and Byzantine Mediterranean cultures to the liturgical manuscripts found in the far northwestwardly British Isles.

The Gospels of St. Augustine. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 286 f.208r, John 1

6th Century Italian Vulgate said to have accompanied Augustine to Canterbury.

The standard Biblical text in England seems to have been the Vulgate translation of the Bible. The use of the Vetus Latin or Old Latin bible seems to have

persisted longer among the Irish, the pocket Gospel Book of Mulling being an

example, written and illuminated in the second half of the 8th century.

Portrait of John the Evangelist holding a book and the opening page of John 1.

Book of Mulling, Trinity College Dublin, MS 60, ff. 81v-82. Second half of 8th century

https://i1.wp.com/www.tcd.ie/Library/early-irish-mss/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/082-MS60_15_LO_crop_750.gif?resize=474%2C497

One surviving link between Rome and Naples and the scriptoria

of Northumbria is the British Library manuscript Royal 1 B VII. This

gospel book dates to 700 to 749 and was created in Northumbria. This is a

remarkably complete Vulgate translation gospel book including Jerome’s letter

to Pope Damasus, Jerome’s commentaries on each of the four gospels and his

prologues for each of the gospels. There are Eusebian canon tables decorated

with interlacing and human, animal and bird heads. For the gospels of Matthew,

Mark, Luke and John, there are list of festivals in which portions of the

gospel are to be read.

British Library MS Royal 1 B VII f.130v. John 1. Made in Northumbria about 700-749.

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=royal_ms_1_b_vii_f130v

The gospel book Royal 1 B VII is rather unlike its elaborately decorated cousin the Lindisfarne gospels. It has been suggested that both books derive from a now lost exemplar from Neopolitan Italy, not copied from the other. The Royal 1 B VII gospel book includes the commemoration of St. Januarius, for example. Januarius was a legendary bishop of Beneventum who was supposedly martyred during the reign of the Roman emperor Diocletian. He is a patron saint of the diocese of Naples. The commemoration appears also in to Lindisfarne gospels. Several theories suggest that this now lost gospel book was brought by Hadrian to Canterbury when he became abbot and where Benedict Biscop might have learned of the text. Another theory is that Benedict Biscop might have brought back a Neapolitan gospel book or bible during his book buying trips. The third suggestion is the Ceolfrith might have brought such a book from Italy when he returned to Northumbria with Benedict Biscop.

Thus, in the year 710, two great leaders of the English

Church, Bishop Wilfred and the Abbot Hadrian died. The major scriptoria of the

north, Landisfarne and Wearmouth-Jarrow, and probably others in Northumbria

were producing memorable manuscripts such as the Gospel Book of St. Cuthbert,

Royal 1B VII, the Lindisfarne gospels, and the Codex Amiatinus. Bede was teaching and writing at the Abbey of

St. Paul at Jarrow. In another decade, he would be writing his Ecclesiastical

History of the English People or Historia

ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum. Fortunately, it would be another 80 or so

years before the dread Viking ship prows appeared at Lindisfarne and later

Wearmouth-Jarrow and Iona. In was in this period when classical learning was

contending with the artistic traditions of the Irish, Angles and Saxons, that

the Ruthwell Cross and the related Bewcastle Cross were carved.

[i] Veronica Ortenburg.

“Archbishop Sigeric’s Journey to Rome, 990” in Michael Lapidge, Malcolm Godden,

Simon Keynes, (eds) Anglo-Saxon England 19. Cambridge University Press, 1990,

pp. 197-246.

[ii] Michael Lapidge, “The

Career of Archbishop Theodore,” in Lapidge, Michael. Archbishop Theodore:

Commemorative Studies on His Life and Influence. Cambridge Univ Pr, 2006, at p.

26.

No comments:

Post a Comment